How Do Students Learn About Intelligence Briefings? How About Briefing a Former CIA Intelligence Officer

One University of New Brunswick professor has her students brief a former CIA intelligence officer to help them learn to think on their feet.

How do you teach students to prepare and deliver a high-level intelligence briefing to a senior political leader? Dr. Sarah-Jane Corke (PhD’00), an associate professor in the department of history on the University of New Brunswick’s (UNB) Fredericton campus, has her students brief a former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) intelligence briefer, a highly stressful but effective form of experiential learning. This can be “extremely intimidating” to the students, Corke said — and she sees that as a good thing.

“I’d rather my students have this experience of briefing someone they find intimidating in the classroom, than have them do it, for the first time, in a work environment. These experiences teach students to think on their feet,” she said.

“They learn there are different ways of writing for different audiences. For instance, a normal intelligence estimate would go through five to seven layers before it reaches the president,” Corke said.

Experiential learning in the classroom

Corke’s academic focus is the domestic roots of Cold War policy and the history of the Central Intelligence Agency. She teaches two classes employing experiential learning: In “HIST 3461 The CIA in American History,” students give an intelligence briefing to a former CIA intelligence briefer, while in “HIST4465 The Cuban Missile Crisis,” students act in a crisis simulation.

In HIST 3461 students work on long intelligence estimates, as well as shorter intelligence analyses of the kind that go into the American president’s daily briefing. They also must give an oral presentation “to someone they’ve never met and someone who has had a very high-profile job in government service,” said Corke.

David Priess played this role last year. Corke described him as “probably the most impressive briefer to work in US intelligence.” He worked in the CIA during the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations. Priess, who is now retired from the CIA, writes and lectures and serves as the chief operating officer of a Washington think tank.

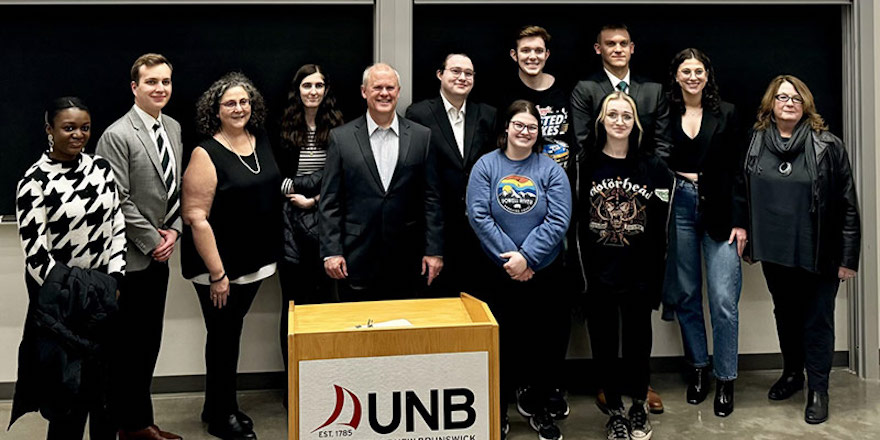

Guests this semester were former CIA intelligence analysts Cynthia Storer and Mark Stout.

In History 4465, students engage in a crisis simulation of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. Corke has each of them assume a character from President John F. Kennedy’s executive committee of the National Security Council (EXCOMM). Throughout the semester they read about and become that person. In the three-hour class they craft a letter to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev.

“I will have different students come into the classroom with additional pieces of information that they need to take into consideration when drafting that letter,” she says. Someone then comes in playing the role of the president — usually someone with “an intimidating presence” — who must be briefed on the letter.

“They learn to work as a group, negotiate with peers, and develop the skills needed for a leader in a group environment. They also learn the ability to gauge what skills each player brings to the table, and what their own strengths and weaknesses are,” said Corke. “We teach our students to write, to speak in public, and to think critically about the world.”

CIA guest speakers share their stories

In addition to the classroom exercises Corke also brings in guest speakers to talk to her students. For example, on March 14, former CIA analyst Storer delivered a lecture relating how she came to realize the danger of an emerging terrorist group and was the first in the CIA to call it Al-Qaeda — because, she said, it was literally on their letterhead.

Storer detailed how she and other CIA analysts, mostly women, tried to get the word of the threat up the chain during the presidencies of Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. She is featured in Liza Mundy’s book The Sisterhood, which recounts the efforts of these analysts.

Their concerns were downplayed until it was too late, partly due to sexism and partly due to entrenched beliefs by superiors who dismissed Al-Qaeda as a serious threat. Siloed intelligence agencies made things worse, and it was exceptionally difficult, if not impossible, to search the voluminous paper archives.

Then 9/11 happened. She watched it on a colleague’s monitor. “I looked over my cubicle wall and the second plane flew in. I’m like, ‘That’s it. We missed it,’” Storer said. Eventually funding and institutional reform came, but it was too late for those who died that day.

Mark Stout, who before entering academia spent 21 years in American national security, lectured on American intelligence history on March 18. Stout’s theory is that while organized intelligence gathering and analysis had been abandoned by the United States immediately after the Civil War, by the end of the First World War most of the modern pillars of American intelligence were in place to be improved on during the Second World War and the Cold War. Stout played the role of the president in this year’s briefing simulation.

Hannah MacLeod, a student who played the Director of National Intelligence in the simulation, stressed the importance of the exercise. “He was able to put us into a role-playing exercise that allowed us to really get into the environment of the intelligence communities. It really led us to think on the spot and think about how these people interact in their day-to-day life,” MacLeod said.

Student Ell Gignac also enjoyed the interactive part of classes and the guest lectures. “It’s interesting to learn about the people who are behind the stuff that happens in our society, especially since I like foreign relations and international relations.”

Student Bellamy Wright agreed. “Dr. Corke’s lectures are very good. But having this is someone’s personal experience. It’s their own story that they’re able to tell us so it adds another level of authenticity to it.”

Students have gone on to work at the Canadian Security Intelligence Service

Corke said students often arrive with inaccurate ideas of intelligence agencies, gleaned from popular culture, which she must dispel. Corke cited political scientist Amy Zegart, who argues that often “spy-themed entertainment” stands in for reality. Fictional spies are shaping public opinion and real intelligence policy. Worse, those who watched the television series 24 were statistically more likely to approve of harsh interrogation methods like waterboarding.

Some students have gone on to work at the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS). Others have told her they adopted her techniques in subsequent work. A Queen’s University law student who won a moot court competition said she had triumphed due to learning effective methods of argument from Corke. “It is not just about memorization of facts. It’s about interpretation. It’s about argument,” Corke said.

Student Bee Hughes called Corke’s experiential learning approach “amazing.” “The way that she makes us gather information for class and then share it makes us think very critically. You have to analyze a lot of what’s going on in the world right now.”

Learn more about University of New Brunswick